Long Covid remains a mystery, though theories are emerging

Millions of people around the world are believed to suffer from long Covid yet little remains known about the condition -- though research has recently proposed several theories for its cause.

Between 10 to 20 percent of people who contract coronavirus are estimated to have long Covid symptoms -- most commonly fatigue, breathlessness and a lack of mental clarity dubbed brain fog -- months after recovering from the disease.

The US-based Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME) estimates that nearly 145 million people worldwide had at least one of those symptoms in 2020 and 2021.

In Europe alone, 17 million people had a long Covid symptom at least three months after infection during that time, according to IHME modelling for the World Health Organization (WHO) published earlier this month.

These millions "cannot continue to suffer in silence", WHO Europe director Hans Kluge said, calling for the world to act quickly to learn more about the condition.

Researchers have been racing to catch up but the vast array -- and inconsistency -- of symptoms has complicated matters.

More than 200 different symptoms have been ascribed to long Covid so far, according to a University College London study.

- 'Fatigue in the background' -

"There are no symptoms that are truly specific to long Covid but it does have certain characteristics that fluctuate," said Olivier Robineau, the long Covid coordinator at France's Emerging Infectious Diseases research agency.

"Fatigue remains in the background," he told AFP, while the symptoms "seem to be exacerbated after intellectual or physical effort -- and they become less frequent over time".

One thing we do know is that people who had more severe initial cases, including needing to be hospitalised, are more likely to get long Covid, according to the IHME.

Researchers have been pursuing several leads into exactly what could be behind the condition.

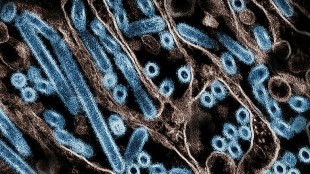

A study published in the journal Clinical Infectious Diseases in September found that Covid's infamous spike protein --- the key that lets the virus into the body's cells -- was still present in patients a full year after infection.

This suggests that viral reservoirs may persist in some people, potentially causing inflammation that could lead to long Covid-like symptoms, the researchers said.

If they are right, a test could be developed to identify the spike, potentially leading to one of the great and elusive goals of long Covid research -- a clear way to diagnose the condition.

However, their findings have not been confirmed by other research, and several other causes have been proposed.

- 'Data not very solid yet' -

One leading theory is that tissue damage from severe Covid cases triggers lasting disruption to the immune system.

Another suggests that the initial infection causes tiny blood clots, which could be related to long Covid symptoms.

However "for each of these hypotheses, the data is not very solid yet", Robineau said.

It is most likely that "we are not going to find a single cause to explain long Covid", he added.

"The causes may not be exclusive. They could be linked or even succeed each other in the same individual, or be different in different individuals."

A way to treat the condition also remains elusive.

For the last year, the Hotel-Dieu hospital in Paris has been offering long Covid patients a half-day treatment course.

"They meet an infectious disease specialist, a psychiatrist, then a doctor specialising in sports rehabilitation," said Brigitte Ranque, who runs the protocol dubbed CASPER.

"In the team's experience, a majority of the symptoms can be attributed to functional somatic syndromes," she said. These are a group of chronic disorders such as chronic fatigue and fibromyalgia that have no known cause.

Cognitive behavioural therapy, a psychological approach often used for those syndromes, is used to treat long Covid alongside supervised physical activity, Ranque said.

"The patients are brought back in three months later. The majority of them are better. More than half say they are cured," she told AFP.

"But about 15 percent did not improve at all."

(H.Leroy--LPdF)